String types exist as a means to represent text. Rust string types are more complicated compared to other languages, primarily because Rust forces the programmer to consider more of the underlying implementation details of strings when writing code, rather than abstracting it away. This is due to Rust’s emphasis on memory-safety. This article aims to explain the basics of strings in detail and where relevant clear diagrams will be used to help illustrate the internal structure of strings and to simplify complex concepts.

Contents

- What is a string?

- Brief overview of memory

- Memory representation of string types

- String ownership

- A note about lifetimes and traits

- Next steps

- References

What is a string?

A string is a type of collection - a data structure that stores multiple values, which together encode characters to represent text. Under the hood, string data itself is really just a sequence of bytes that the computer is able to interpret as being text. The character encoding system in Rust is UTF-8. This stands for Unicode Transformation Format, 8-bit encoding, which gives us a clue as to what this system is doing.

Unicode is a character encoding standard to represent text; a unique value (called a code point) is assigned to each character that exists to uniquely identify that character. You can think of it as a classification system for characters, just as we have classification systems for diseases and species of animals. Code points are written in the format of U+ followed by a hexadecimal number. For example ‘A’ is represented by U+0041.

UTF-8 is the encoding system which takes each code point defined by unicode and converts it to a sequence of 1-4 bytes (chunks of 8 bits). It is backwards compatible with a different and more simple encoding system called ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange), and extends ASCII (which only encodes 128 characters) to handle a much wider variety of characters. In UTF-8, the first 128 characters are equal in value to the ASCII characters and are encoded using 1 byte. For other characters, UTF-8 uses multiple bytes. See Figure 1 for some examples.

| Character | Code point | ASCII (7 bits) | UTF-8 (8 bits) | Decimal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | U+0041 | 1000001 | 01000001 | 65 |

| B | U+0042 | 1000010 | 01000010 | 66 |

| é | U+00E9 | - | 11000011, 10101001 | 195, 169 |

| 你 | U+4F60 | - | 11100100, 10111101, 10100000 | 228, 189, 160 |

Figure 1: Table showing examples of characters, their unicode code point values, their binary value in ASCII and UTF-8 and the corresponding decimal values. Characters in bold are encoded by ASCII. Note that ASCII encodes characters using 7 bits, and UTF-8 uses 8 bits.

In Rust, the two most commonly used string types are String and &str. Below are some examples of how they can be used - you may recognise similar string functionalities that exist in most programming languages.

// declaring strings

let wir_str = "Women In Rust";

let wir_string = String::from("Women In Rust");

// concatenating

let women = String::from("Women ");

let in_rust = String::from("In Rust");

let women_in_rust = women + &in_rust;

// appending

let mut women = String::from("Women ");

women.push_str("In Rust");

women.push('!');

The differences between String and &str can be confusing when you first encounter them but this is made much clearer by understanding their underlying memory representations.

Brief overview of memory

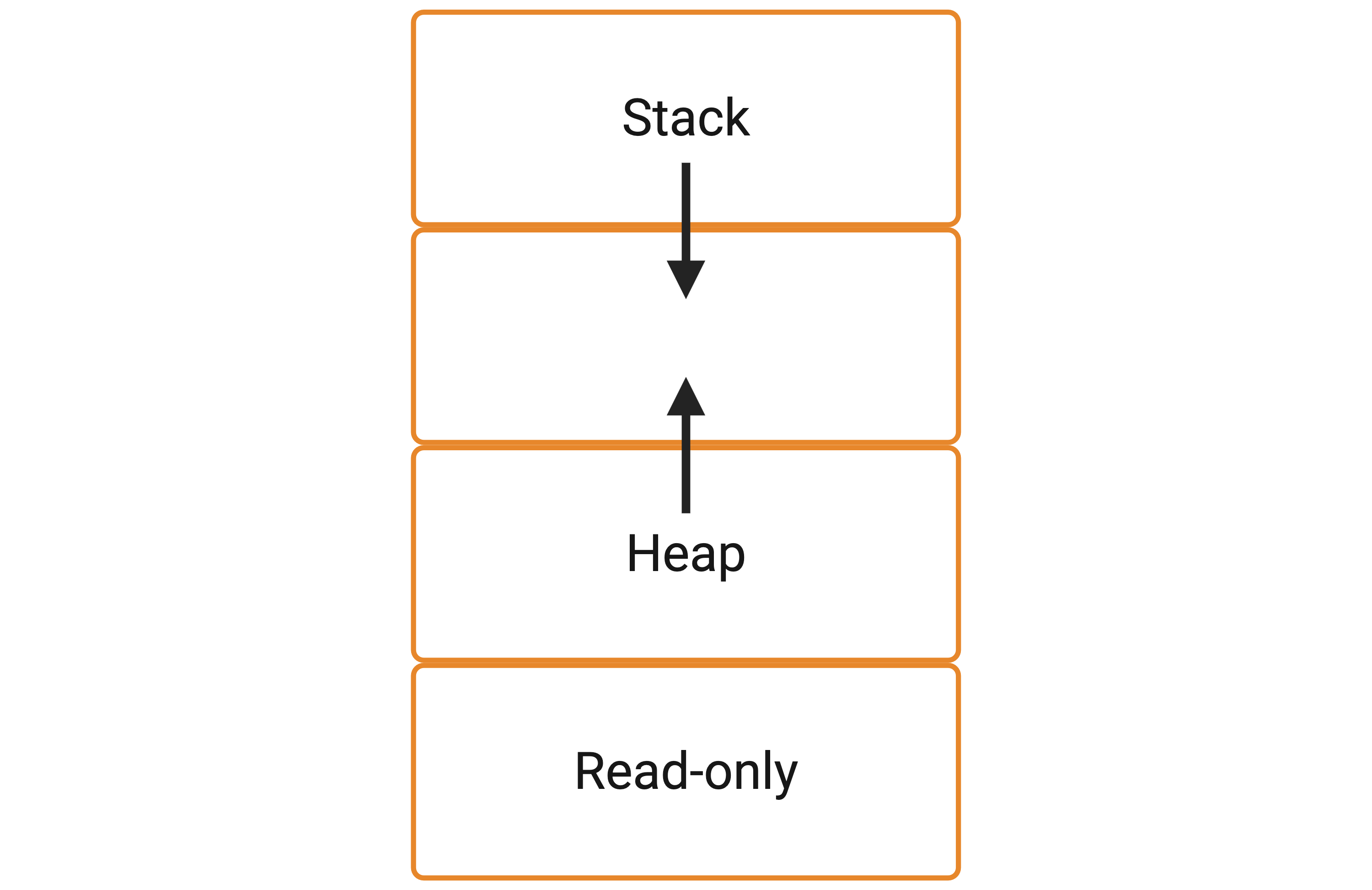

When a program runs, the operating system and underlying hardware create a virtual address space for the program which it maps to actual physical memory. The program operates as if it has access to a large, continuous block of memory, represented by virtual memory addresses. This is a concept called virtual memory. Virtual memory is split into different sections, with differing characteristics and purposes. The main areas which bear relevance to Rust string types are the stack, heap and read-only section (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: A simplified depiction of virtual memory.

Figure 2: A simplified depiction of virtual memory.

Below are the main points to be aware of:

Stack

- Used to store data with a size which is fixed at compile-time, meaning that its size cannot change during runtime. For example, primitive type variables and function arguments are stored here.

Note: primitive types are simple types that are built into the Rust language. See (5) in the references for more details.

- Memory can be allocated and deallocated quickly.

- Smaller with less memory available than the heap.

Heap

- Used to store data with a size which is not fixed at compile-time, meaning that its size can change during runtime. For example, dynamically-sized arrays are stored here.

- Slower memory allocation and deallocation than the stack.

- Larger with more memory available than the stack.

Read-only section

- Here the machine-level instructions generated during compilation are stored and marked as read-only to prevent modification during execution.

- It also contains data which exists and is valid for the entire lifetime of the program and does not change, for example constant variables.

Memory representation of string types

Understanding how the different string types in Rust are represented under the hood makes it much easier to understand their functions and use cases. We will go through the main types below.

String

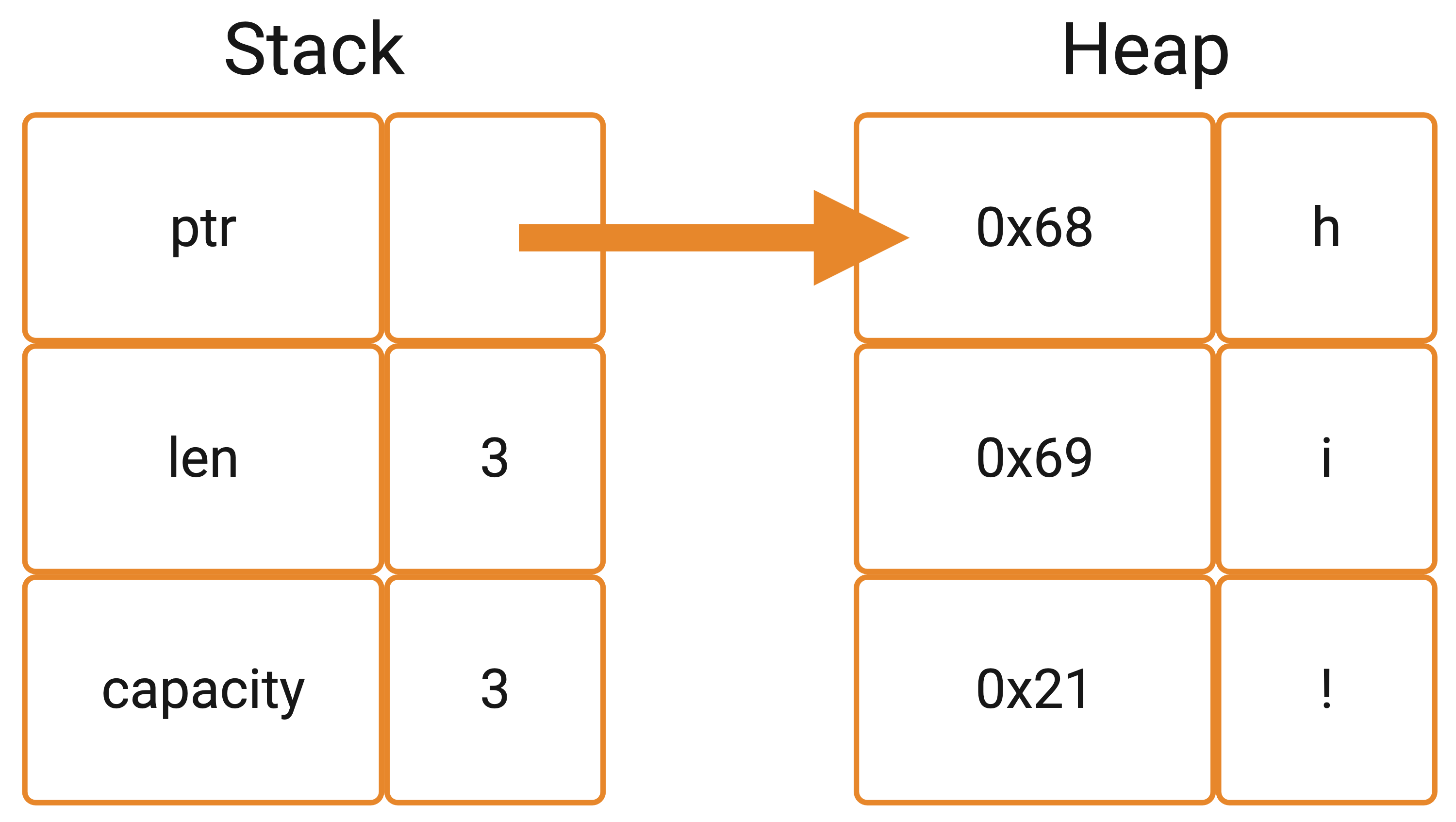

Figure 3: Diagram showing how the

Figure 3: Diagram showing how the String type is represented in memory.

A String in Rust consists of two different parts:

String data (right of Figure 3)

This consists of the sequence of bytes that represents characters. In the example, all characters are represented by 1 byte. String data is stored on the heap and its size is not fixed at compile-time; the size of the data can grow and shrink as the program runs. As long as a String is declared as mutable with the mut keyword, its data can be altered during runtime.

String struct (left of Figure 3)

This is a fat pointer, which contains a pointer to the string data on the heap, and the capacity (allocated memory) and length (actual space used) of the string data.

We can demonstrate the String structure using code:

let hello = String::from("hi!");

// prints the stack memory address where the String struct is stored

println!("String struct address: {:p}", &hello);

// prints the heap address where the string data is stored

println!("String data address: {:p}", hello.as_ptr());

The output of the above looks something like this:

String struct address: 0x7ffc51f2cb88

String data address: 0x5f0232170b10

This shows that the two parts of the String reside in different areas of memory.

&String

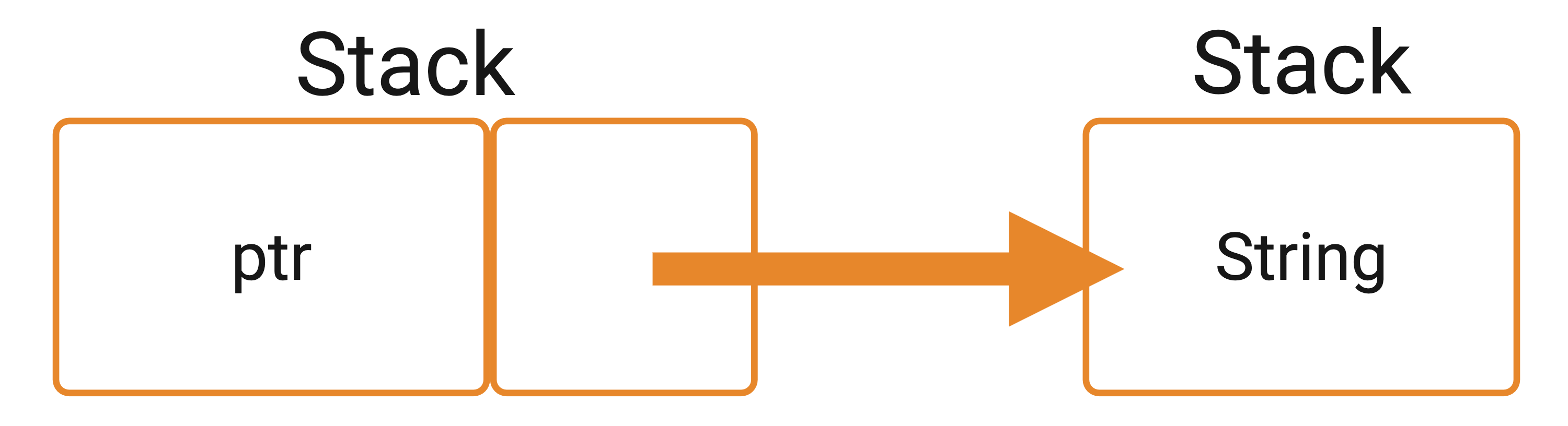

Figure 4: Diagram showing how

Figure 4: Diagram showing how &String is represented in memory.

This is a reference to a String, which points to the String struct stored on the stack. As we saw above, this string struct itself contains a pointer to the actual string data. &String is generally an unnecessary level of indirection if an immutable reference (&str) is sufficient. Deref coercion is a feature that means Rust automatically converts &String to &str when needed, so &String is redundant in most cases. For more information about this, see the resources in the references.

str

Figure 5: Diagram showing how the

Figure 5: Diagram showing how the str type is represented in memory.

let my_string: &str = "hi!";

This is a string literal, consisting of a sequence of bytes that represent characters forming text, stored in the read-only data section of memory during compilation. String literals are immutable by default, meaning they cannot be modified after they are created.

Notice that the type of my_string is &str, not str. This is because str is an unsized type. The size of str can vary depending on the length of the string, and because of this, its size is not fixed. The compiler cannot determine how much memory to allocate for string literals at compile time, since the size of the string depends on the number of characters, which is only known at runtime.

This is why you cannot use str directly as the type of a variable. Instead, string literals are always represented as a reference to str (&str). The &str type is sized, meaning it has a fixed size at compile time. It consists of a pointer to the string data and a length field, which is known at compile time (see below).

&str

Figure 6: Diagram showing how

Figure 6: Diagram showing how &str is represented in memory.

Figure 6 shows two examples of &str, which consist of a pointer which points to the string data stored elsewhere, as well as the length of that string data. &str is always immutable and allows for read-only access to string data. &str is a slice type, which is a reference to a contiguous sequence of elements (in this case, bytes representing characters). Since &str is essentially a slice of a string, it points to a portion of string data which can be either from a string literal (slice_from_literal) or from heap data (slice_from_heap).

Consider the following code and how it relates to the above diagram:

// Points to string literal stored in the read-only data

let slice_from_literal: &str = "hey";

let heap_string = "hey".to_string();

let slice_from_heap: &str = &hey[..];

slice_from_literal is assigned to the string literal “hey”. slice_from_heap is assigned to a slice of heap_string, which is a reference to the string data inside the String object. This means that slice_from_heap can efficiently gain read-only access to the string data from heap_string.

Note that Rust does not allow direct integer indexing of strings - consider the following example:

let word = "你好吗".to_string();

let shorter_word = &word[1..];

This code attempts to access the second character onwards and assign it to shorter_word. However, if you try running this code you will get the following error:

byte index 1 is not a char boundary; it is inside '你' (bytes 0..3) of `你好吗`

Recall that Rust uses UTF-8 to encode characters, and non-ASCII characters (such as the Mandarin characters above) are encoded using multiple bytes. This code actually attempts to access the second byte rather than the second character, therefore as the error message explains, it tries to slice within the first character which Rust does not allow.

Consider a second example:

let a: String = String::from("hello");

let b: &str = a[1];

Even though all of the characters in “hello” are ASCII characters and encoded using 1 byte, and therefore there is no risk of indexing in the middle of a character, Rust still does not allow this. If you try running this you will get the following error:

The type `str` cannot be indexed by `{integer}`

So Rust protects us from making any unsafe assumptions about byte boundaries, and disallows direct integer indexing. To access characters or bytes, instead you can use the .chars() or .bytes() method respectively.

String ownership

Rust’s ownership and borrowing model handles the memory of the String type in a way that’s both safe and efficient, eliminating the need for a garbage collector.

Below are some rules to keep in mind when thinking about ownership in Rust:

- Each owned value has a single owner.

- When the owner goes out of scope, or when ownership is reassigned, the value is dropped, its memory is freed and it is no longer valid.

- Ownership can be transferred (or moved), but it cannot be shared without borrowing.

Let’s go through some examples to illustrate the above.

Example 1: scopes

{

let s = String::from("I love rust!");

}

In the above code, s owns the String created with “I love rust!” (rule 1). s is created within a scope defined by the curly brackets. As soon as the scope ends, after the closing curly bracket, s goes out of scope and Rust automatically drops the value it owns, and its associated memory is freed (rule 2). This means after the block ends, s is no longer accessible, and attempts to use s outside its scope will result in an error at compile-time:

error[E0425]: cannot find value `s` in this scope

println!("{}", s);

^

help: the binding `s` is available in a different scope in the same function

--> src/main.rs:3:13

let s = String::from("I love rust!");

^

Example 2: reassignment

let mut string_example = String::from("hey");

println!("String struct address: {:p}", &string_example);

println!("String data address: {:p}", string_example.as_ptr());

In the first line, a mutable String is defined. We then print the struct and string data addresses for string_example. If this is run, the result would look something like this:

String struct address: 0x7ffd5b428610

String data address: 0x611b31bbeb10

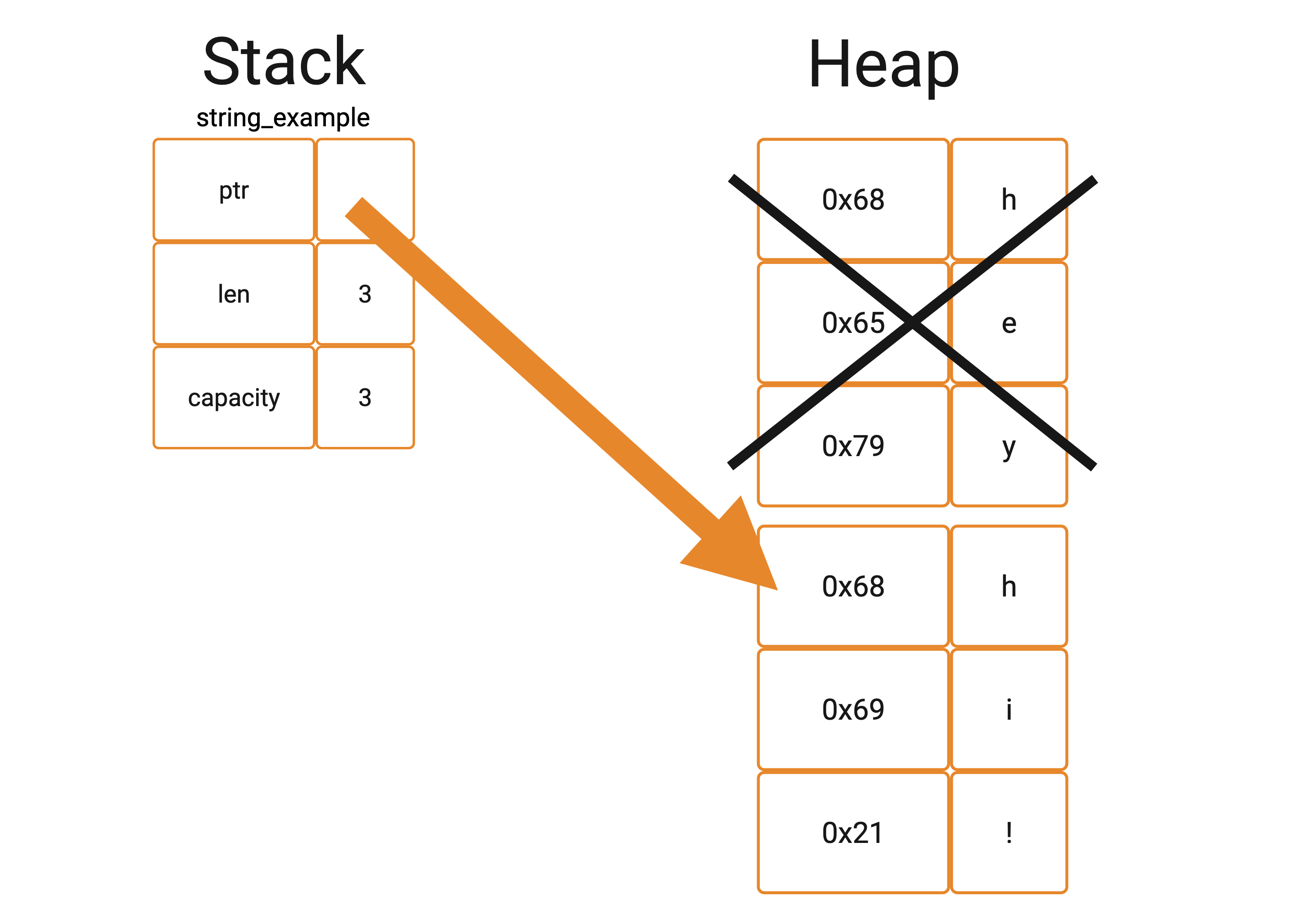

This is also shown in the diagram below:

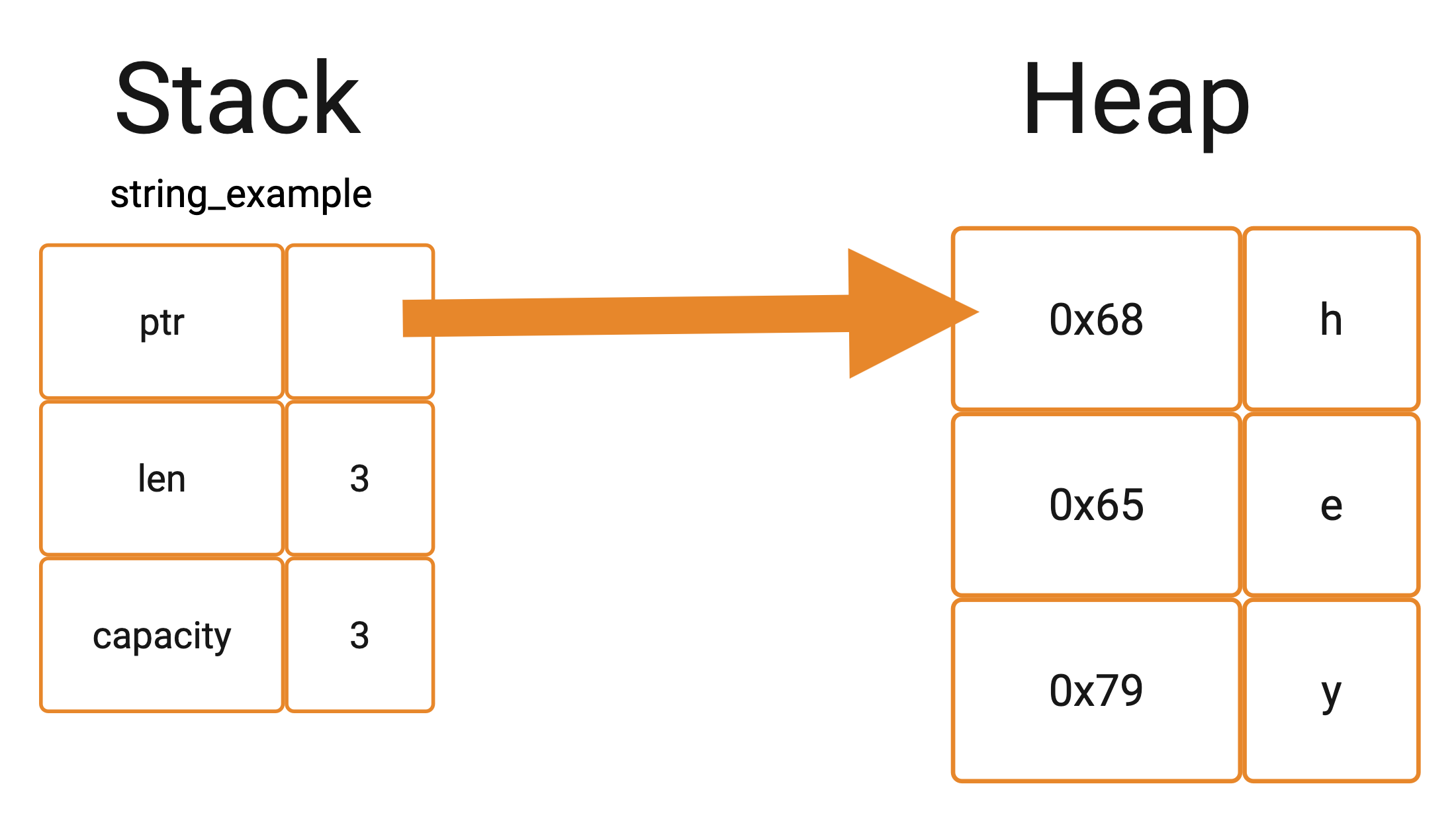

Figure 7: Diagram showing the initial assignment of the String

Figure 7: Diagram showing the initial assignment of the String

In the code below, string_example is re-assigned to a different String. Note that when the struct and string data addresses are printed again, the address of the string struct does not change, but the address of the data it points to does change.

string_example = String::from("hi!");

println!("String struct address: {:p}", &string_example);

println!("String data address: {:p}", string_example.as_ptr());

The output would look something like this:

String struct address: 0x7ffd5b428610

String data address: 0x611b31bbeb30

Given that there is no longer any owner of the first String, it is dropped and its memory is freed (rule 2). The pointer in the hey struct then points instead to the new string data on the heap. This is shown in the diagram below:

Figure 8: Diagram showing reassignment and dropping of the previous value when a variable is reassigned.

Figure 8: Diagram showing reassignment and dropping of the previous value when a variable is reassigned.

Example 3: ownership transfer

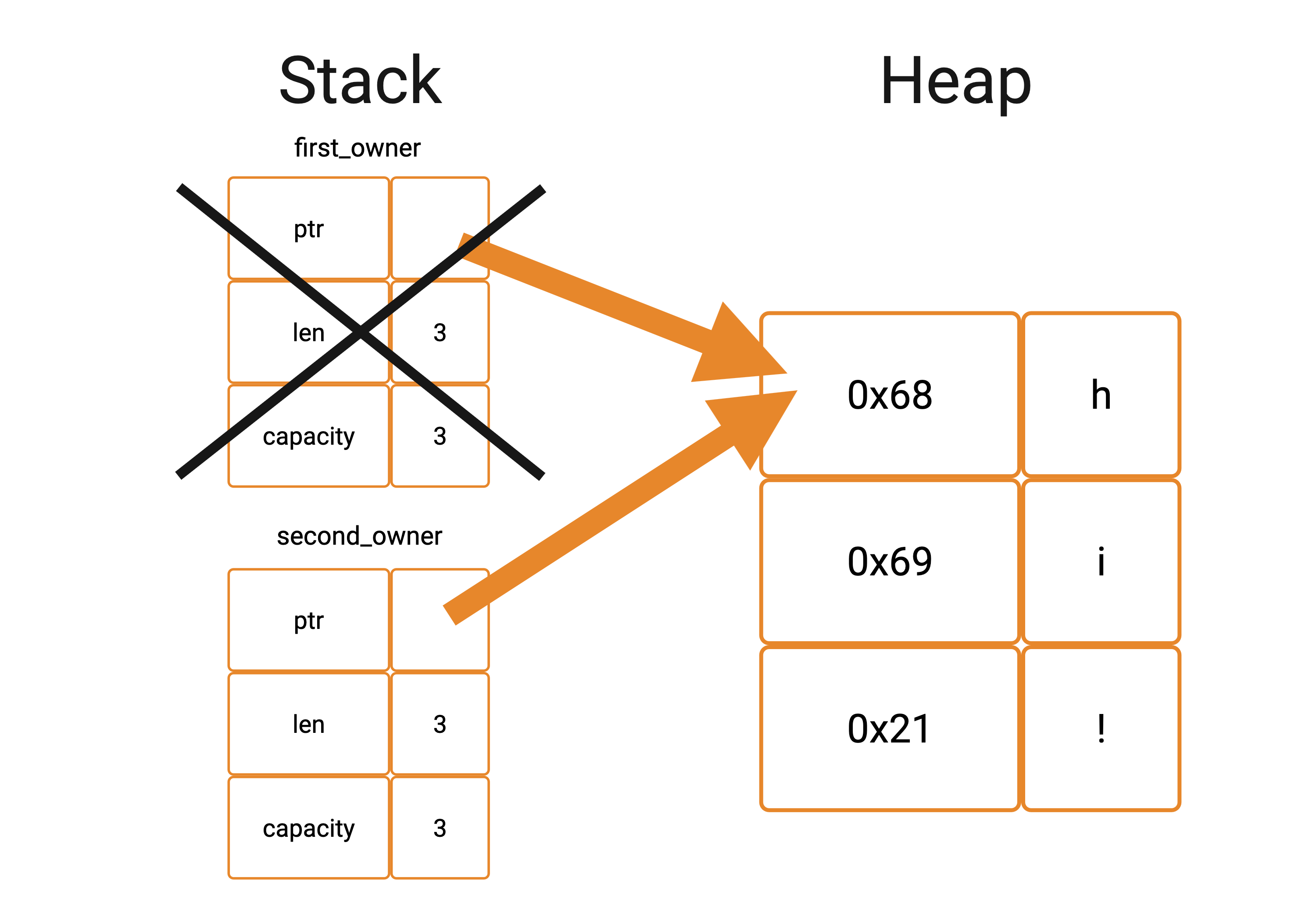

Let first_owner = String::from("hi!");

let second_owner = first_owner;

In this example, first_owner is initially the single owner of the String “hi”. In the second line, a new variable second_owner is assigned to first_owner. Given that each owned value can only have a single owner (rule 1), ownership of the String is transferred from first_owner to second_owner, meaning that first_owner is no longer valid and no longer owns the String (rule 3). The below diagram shows what is happening in memory:

Figure 9: Diagram showing ownership transfer from one variable to another.

Figure 9: Diagram showing ownership transfer from one variable to another.

If you were to try to subsequently access first_owner, you would get a compile-time error:

let accessing_first_owner = first_owner.push_str(" how are you?");

error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `first_owner`

let first_owner = String::from("hi!");

move occurs because `first_string` has type `String`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

let second_owner = first_owner;

-- value moved here

let accessing_first_owner = first_owner.push_str(" how are you?");

^^ value borrowed here after move

help: consider cloning the value if the performance cost is acceptable

let second_owner = first_owner.clone();

++++++++

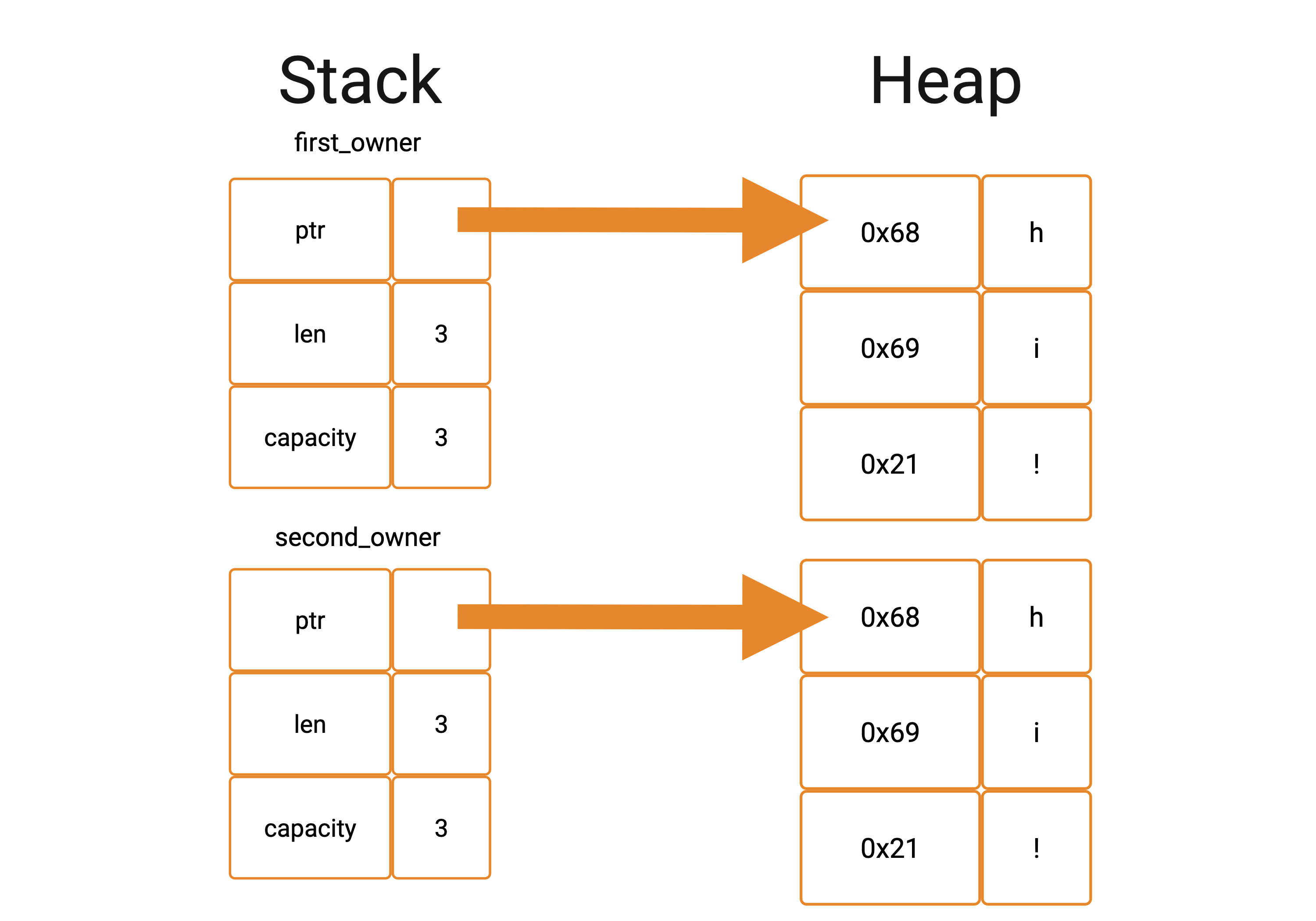

Example 4: cloning

Note that the “help” part of the error message above in Example 3 indicates how we can duplicate the underlying string data on the heap so that both first_owner and second_owner can own independent copies of the same data. This can be done using the clone() method:

let second_owner = first_owner.clone();

Below is a diagram that shows what happens in memory when cloning occurs. Note that the error message in Example 3 recommended “consider cloning the value if the performance cost is acceptable.” This refers to the fact that cloning creates two separate copies of the string on the heap, which uses up more memory and can have a performance cost because of the need to duplicate the data. Therefore, while cloning can be useful, it should be used carefully, especially when dealing with large data.

Figure 10: Diagram showing

Figure 10: Diagram showing String cloning.

Ownership and borrowing in Rust offer several key advantages over traditional memory management methods, for example garbage collection. The most significant advantage is that Rust enforces memory management at compile-time rather than runtime, resulting in less performance overhead during program execution. This means that memory-related errors, such as use-after-free, dangling pointers, and memory leaks, are caught during compilation rather than while the program is running. There is also no automatic duplication of String data unless explicitly requested by the programmer through cloning. This allows for more efficient memory usage and avoids unnecessary overhead from automatic copying.

A note about lifetimes and traits

Lifetimes and traits play a crucial role in memory management in Rust. Lifetimes are used to ensure that references (e.g. &str) do not outlive the data they point to, preventing dangling references and ensuring memory safety at compile time. Traits define behavior that types must implement, and they are integral in managing borrowing and ownership. For example, you may have noticed that the error message in Example 3 mentions that type String does not implement the Copy trait. Lifetimes and traits are important concepts to understand but they are beyond the scope of this article - if you are interested in learning more about this, drop me a comment below and I’ll write an article, or take a look at the references at the end.

Next steps

This article explored the basics of strings in Rust, focusing on the two main types: String and &str. These two types cover most common use cases when working with strings in Rust. However, Rust also provides more advanced string types and functionalities for more complex scenarios. More advanced concepts including lifetimes, traits and deref coercion also play a crucial role in string manipulation and memory management in Rust. Further resources to learn more about these topics can be found in the references.

References

The Rust Programming Language Book

The official, free online book about Rust, covering strings, ownership/borrowing, lifetimes, traits and more.Programming Rust (2nd Edition)

By Jim Blandy, Jason Orendorff, & Leonora F. S. Tindall

A comprehensive guide to Rust with detailed explanations of core concepts.Rust Documentation - String

Official documentation for Rust’sStringtype.Rust Documentation - str

Official documentation for Rust’sstrprimitive type.Rust By Example - Primitives

Describes all of Rust’s primitive types with examples.Computer Systems: A Programmer’s Perspective (3rd Edition)

By Randal Bryant & David O’Hallaron

Foundational text on computer systems.